By: Stacey Vanden Bosch

I recently read a post by Dr. Aradhana Mudambi entitled, “When your dual language program isn’t really a dual language program.” In it she claims, “There has been a false dichotomy between separation of language and translanguaging.” She goes on to claim that programs not enforcing a strict separation of languages, at least for the adults (teachers), are not really dual language programs.

I wholeheartedly agree! But, I’ll take it a step further.

Separation of language is not only for teachers; it’s for students too. Don’t get me wrong, I agree with translanguaging scholars that we NEED to address the inequities for multilingual students entering schools that have historically privileged English speakers. (Bhasin, et al, 2023, Hamman, 2018). I also agree completely with translanguaging practices like encouraging students to draw on their entire linguistic repertoires and celebrating what multilingual learners bring to classrooms (Hamman, 2018, p. 25).

I simply believe that all of this can be done while maintaining the separation of language that values and expects Spanish language use. In fact, I know it. I have observed it in classrooms of teachers committed to the Language First approach. (Check out the link at the end of the post to learn more.)

In part one of this two-part blog post, I want to explore why separation of language is important if we want students to meet the goal of bilingualism and biliteracy.

In part two, I want to share how you can get started with an important tool, called LIOPT (Language of Instruction Only Policy and Timeline). Stay tuned!

research is clear

Both emerging bilinguals, Spanish and English-dominant students tend to prefer English. In fact, many dual language students ultimately self-report that they feel more proficient in English. As a result, they use it far more than Spanish. Some experts refer to this as “English takeover.” The overuse of English means less attention to Spanish. This not only undermines the goal of bilingualism and biliteracy but also diminishes the perceived value of Spanish or other minority languages. That strikes me as the antithesis of trying to change a system historically designed to privilege English speakers.

And, the truth is:

- MORE time and instruction in ENGLISH does NOT lead to increased performance on standardized measures of achievement in English (particularly for students who enter programs as Spanish-dominant or emerging bilinguals)

- MORE time and instruction in SPANISH, however, lead to higher levels of bilingualism and biliteracy at no cost to English achievement (for both Spanish and English-dominant students).

To dig a little deeper, let’s look at two factors that influence the degree of proficiency children or adults will attain according to Second Language Acquisition research.

- intrinsic motivation

- time and intensity of exposure

intrinsic motivation

In the United States, from an early age, students are sent subtle (and not so subtle) messages about the importance of English versus Spanish. Let me give you some examples. Think about the slight grimace we sometimes see on a retail clerk’s face when helping someone unable to communicate clearly in English. Or think about high stakes tests tied to scholarship money for college. The level of academic ENGLISH required to complete the tasks and receive a competitive score is HIGH. These are two of many examples that send the message to students that proficiency in English is the gateway to opportunity – even power. Because of this, students are intrinsically motivated to acquire English.

For the same reasons, intrinsic motivation is often missing when it comes to Spanish (and other minority languages). In fact, according to respected experts, “there is often a negative attitude toward Spanish-speaking children and their families (Escamilla, 200, p. 101). This negative attitude affects how schools treat Spanish language development and literacy. For example, rather than allowing students to demonstrate they are meeting academic benchmarks in Spanish, many states still require testing in English, even for students in grade levels where English has yet to be formally introduced. Given this historical and current (though hopefully improving) environment, students recognize that Spanish does not bring the same opportunities or level of “power” and thus feel less intrinsically motivated to make proficiency a priority.

time and intensity of exposure

Ironically, the negative attitude and lack of value placed on academic performance and proficiency in Spanish also impacts the other important ingredient to language acquisition: time and intensity of exposure. Think about the structure of many dual language immersion programs. Exposure to Spanish decreases as content becomes more difficult and students require more language skills to navigate learning.

Again, I agree with Dr. Mudambi, dual language programs that offer only advanced language rather than content courses in the LOTE (language other than English) after fifth grade are NOT dual language programs. But again, I’ll take it a step further. Even one content course in secondary programs is not enough time and intensity of exposure to Spanish or other minority languages for students to continue developing bilingualism and biliteracy.

Just think about this:

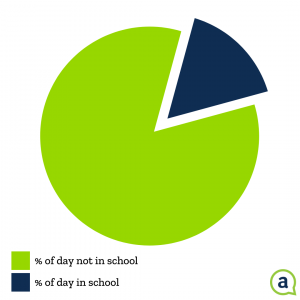

Students are in school only 13.6 percent of their waking hours.

That means the other 86.4 percent of their time is spent outside of school where English dominates most communities. If only a fraction of that 13.6 percent of the time is dedicated to Spanish, it is no wonder dual language students are more proficient in English. It explains why so many of us have reverted to English when our students were unable to navigate complex concepts in Spanish at higher grade levels.

To internally motivate students to use Spanish and to provide them with enough time and space to focus on Spanish, we have to separate it from English. We have to create an environment that privileges its exclusive use to stop English take-over.

The entire education system won’t change overnight, but our individual classrooms can.

Stay tuned for part two when I share how to get started.

Link to Language First webinar: https://addalingua.com/languagefirst/.